Zanzibar, ethical press trips and photographing without consent

Being a black writer on a press trip to East Africa is an experience in an of itself.

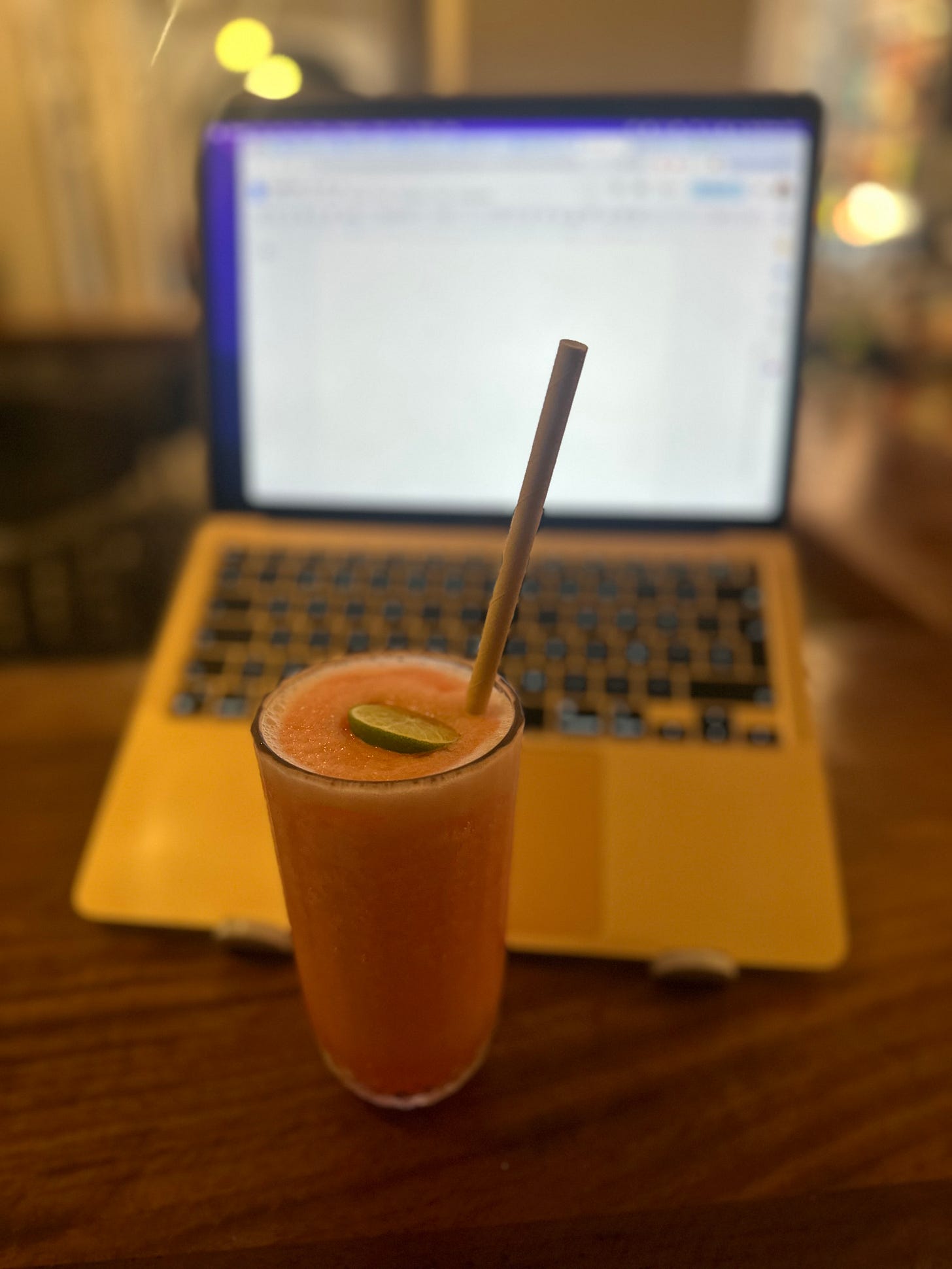

I’m writing this piece at my hotel bar in Zanzibar. The sky is marshmallow-pink like the cocktail beside me. Palm trees sway in the breeze. My hair is damp and piled on top of my head and my face is greasy to touch; a combination of the salt water and sunscreen. I can feel the sand between my toes, but even more potent is the immense feeling of joy that warms me from the inside out (hey, could also be the rum). I'm on a press trip that’s finished and have elected to stay on by myself for a week. I feel grateful, content, but also a little tired. The ethics around press trips are complicated, and dynamics within black-majority countries, even more so.

(Side note: a big hello to anyone reading this and wondering who the hell I am. I’ve decided to relaunch Take World, the name of this newsletter to cover writing, travel writing, entrepreneurship and solo living, after publishing both a travel guide and memoir, and starting writing retreats for women of colour while living in Lisbon. I hope you’ll stick around, every other Tuesday).

I was well looked-after by the company who sent me to Zanzibar and had a great time. And while I was the only British writer, I was not the only black writer (for once), Anna, my ally was a Portuguese journalist of Mozambique heritage. The rest of the group were western European, the average age around 50. I noticed from day one that there seemed to be a fascination with photographing local residents without their consent. I remember walking through a village after touring the Masingini forest, only to witness many people with phones and DSLR’s poised. I watched them snap photos of a woman in a hijab perched on a stool and washing her children in an orange tub outside a small house. No-one asked her consent. This sort of thing happened many times, even though we’d been provided with a welcome pack instructing visitors not to do this.

Imagine for a second if the roles were reversed, if foreigners wandered into the gardens of German or British families, wordlessly taking pictures of young children in a paddling pool? There'd be outrage, calls for deportation. But here in Africa, there’s an understanding that travellers can take what they want. Taking pictures follows a pattern; the systematic extraction and exploitation of land, resources, and people for western gain has been ongoing for centuries.

Then there was the time a woman (not associated with the company who sent me) called hotel staff as “black slaves” over dinner. Another, (who lived on the island) introduced herself to everyone on the trip, except myself and Ana. One journalist expressed annoyance that a four-year-old child had requested money after she’d “asked his permission” for a photo. And on the last night, a male colleague asked: could he please touch my hair?

It’s fascinating to me that ten journalists can fly to the same place yet each of us end up with a different impression of it, based on how we are treated and our own world views. Yet I don’t think anyone else felt what Anna and I did.

Alone on the beach everyone after everyone has departed, I think about how I need to read the 1972 book ‘How Europe Underdeveloped Africa’, by Walter Rodney. I think about conversations on decolonising travel writing and sustainable tourism, how in some newsrooms they are taking shape, but how much ignorance still prevails.

I think about how I’ve seen cameras and microphones brandished as weapons. Where the power dynamic is unbalanced, photography is an extractive act. Taking an image of a subject, using it to craft your own narrative and selling it for profit, reduces agency. None of my colleagues interviewed the Zanzibari people in the street, few even spoke to them. I wonder if they realize that this is a legacy of colonialism—the notion that one must defer to those who look like them—that leads local Muslim women to smile and pose, not out of genuine willingness, but because they feel compelled to do so. These images of Africa are primarily for European consumption, inserted into magazine articles about Zanzibar's beaches, they will only serve to reinforce the stereotype of the faceless, helpless African.

Press trips are a funny way to travel. An anthropological experiment, if you will. Journalists are invited somewhere, plied with food and booze and asked to write stories about it all. You don’t know who you’ll end up with, how manic the schedule will be, or how much of the Kool Aid you’ll have to drink, until you get there. They are often PR pushes for companies, places, or tourism boards, but as a journalist, you don’t have to write what you see. Some journalists live for press trips. This is reflected in the hollow, hostage note-like quality of their subsequent pieces. Others understand that even if you’re on commission, you can use these trips to cultivate multiple stories, for multiple outlets, your own blog or TikTok page, and that you never really work for the PR, or anyone else, for that matter. Some of the best travel experiences of my life have been on press trips (hello, Michelin gastronomy tour around Northern Portugal). Zanzibar, with its 56 varieties of sorbet-like mangoes and ice-white sands, is now on that list.

Some publications, like the New York Times, ban journalists from attending press trips altogether: writers funded by a tourism board or company cannot remain impartial. I see their point; there is an awful lot of free booze. But rules like this mean only a certain type of writer will get to tell travel stories, usually those on staff, or others who can afford to write after self-funded trips. Press trips can be opportunities for new, freelance or low-income writers to make connections and diversify their portfolio.

Being a black journalist in a black-majority country can be both useful and humbling. Moving seamlessly through a space is an incredible asset when it comes to telling a story, even more so if you’re able to speak the local language. You can engender yourself to others more quickly because of a shared heritage or the fact you look like their cousin (this isn’t always a plus). But either way, you feel grounded by the sense of community abroad, the tiny threads of familiarity and adaptiveness that keep us all connected within the diaspora, and that is incredible.

I’ve also been on trips where blending in is a safety risk. Passport privilege is when you receive nice treatment abroad as a tourist, with a passport from a strong (read: often white) country. The level of passport privilege you receive depends not only on your country of origin, but how you sound, and what you look like. It’s intersectional and contextual.

As a black-mixed British traveller, people treat me differently depending on where I am, who I’m with and what part of my identity they perceive at that time. I’ve been mistaken for a prostitute in Cuba and the Dominican Republic after befriending Dutch people in my hostel. I’ve been given preferential treatment by black waiters among an all-white press group at a restaurant in South Africa.

Sometimes, blending in has caused problems with professionalism and being taken seriously and so speaking English loudly has been the only way to restore my status and ensure I received the same treatment as my counterparts. This doesn’t always anger me, it’s just how it is. I can switch between tourist and local, often within the space of an hour and these moments help me better understand the workings of a place, the lives of local people. But when you’re travelling with those who rarely experience being treated as anything but top of the food chain, it can also be isolating.

Yes, take out your tiny violin for me, the travel writer on assignment in paradise, or see the slights I’m describing as proof that the class, colour and racial hierarchies around the world still exist at home and abroad and are completely flimsy and illogical. What I experience on press trips as a black writer, occasionally overlooked, or mistaken for the staff, in an otherwise frothy bubble of air-conditioned transfers and amuse-bouche-meals, is just a tiny fraction of what other people of colour endure on a structural and systemic level in tourism and beyond, every day.

I feel such gratitude that I am able to travel to East Africa for work, to swim in waters that looked like glass, and meet enthusiastic, clear-eyed young women at a local school who tell me about their desire to work in tourism.

I found out that I am half Nigerian a few years ago, and so travel to Africa feels instinctive. I am moved by a lot of what I see and experience here. I feel an indescribable, instinctive pull to find out more about who I am and tell more of the stories I find important. I pitch often to get myself in front of editors (I sent the email that landed me the Zanzibar trip just a week before I left) so I don’t feel “lucky” to be in attendance, but I do often wish there were more writers from a wider range backgrounds around me.

Travel writing in the UK is a hard-to-crack and extremely privileged sector of journalism where commissions are based on clicks and trends, staff jobs are like unicorns, and many publications have homogenous office dynamics. This can result in the same type of stories being told by the same types of people, (although I know a lot of fabulous writers of colour, both established and up-and-coming). And while I think press trips to under-privileged regions can be done responsibly, we need to ensure the right voices are amplified through our writing.

It’s our job to ask the hard questions, instead of blindly accepting the often-sanitised version of a place that is presented to us. We should be pushing against things we don’t believe in. We should be asking PRs to diversify their invite list. Hopefully then, we can get to a point where trips like this don’t involve the photographing of African kids without consent.

Do you think the travel writing industry is changing for the better? What are your opinions on press trips? I’d love to hear thoughts!

Georgina, I found this while debating the ethics of a press trip—the first I was invited to go on! This really resonated with me (both from an ethical perspective and as a WOC journalist), and I'd love to chat with you if you're ever open to it. xx :) —Henah

Beautifully put